Q&A: How you move around a space might shape the future of Architecture

Blending data and design, a new study from Henning Larsen’s Ph.D. fellow Krister Jens aims to shed light on how we can design better communal spaces.

At the University of Cincinnati, students’ choice of study spots might be the key to helping us design better community spaces. Krister Jens, Ph.D. student in data-driven design, is leading a research project through Henning Larsen that aims to creative quantitative data on how our movement and behavior corresponds to the space around us. Using specialized cameras installed at Henning Larsen’s Carl H. Lindner College of Business in Cincinnati, Ohio, his project transforms daily movements into insights on how we can design better workplaces, schools and communities. We sat down with Krister to learn more about the project.

Your work in Cincinnati, monitoring user behavior in interior spaces, is a first for Henning Larsen. What’s the history of this sort of technology within architecture?

I would say the practice of monitoring buildings in this way started only recently, maybe five years ago, perhaps even less. The building sector is still not very widely digitized. We’re starting to see, say, windows that open and close based on the sun’s position, but buildings are still very much developing in this sector. Right now, most of the digitalization in architecture focuses on building functions, not occupants. You can easily access the data streams for heating, cooling, water use and so on because those are very concrete metrics. But human beings are much harder to measure. So building digitalization and smart meters aren’t new, but using them to measure socialization and people’s behavior is a new thing.

Why focus on this? What can we learn from studying how building users occupy the social and closed spaces within this new building?

Open spaces don’t work in isolation. That is to say, open space can be the heart of a building, but enclosed offices and quiet meeting rooms are necessary support functions because the two types of space balance one another.

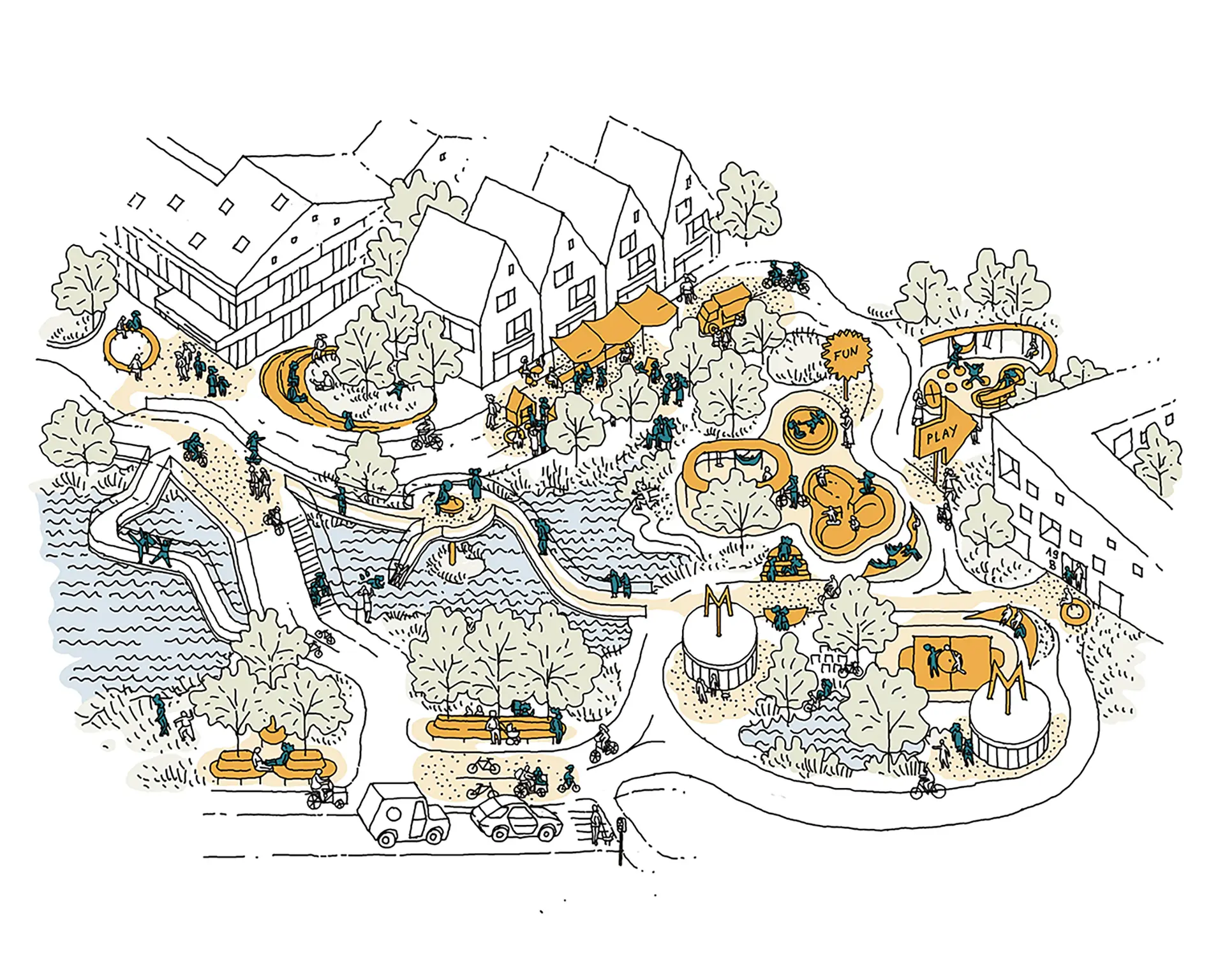

There must be an ideal ratio of open to closed spaces that is best for building users. To what degree do we open up so that we get a synergetic effect, both for the building operation and for user comfort? What do we need to provide for people to work efficiently? What do they need when they’re working alone or in groups, for concentration or collaboration?

These are socio-physical questions because we’re also talking about crowds, personal space, a sense of intimacy, human territoriality, a lot of factors that aren’t physical. You might be in a crowded, talkative atrium but still, feel like you can concentrate. But suddenly, people may leave this ‘collective atmosphere’, and you feel like something’s different, so you also pack up and leave. So my research is helping explore our sense of interpersonal space, how that affects behavior, and how architects can use that for future designs.

Can you talk more about the mechanics of your study? How do you balance mass data collection with a concern for individual user privacy?

I collect booking system data for all the building’s enclosed spaces like meeting and study rooms, so I can see which rooms are used, how often and when. And then I have the open spaces, which I monitor with my five cameras. So I cover both open and closed spaces in the building, and I can get a picture of how often each gets used. And then I look into the activity in these open spaces, of what people actually do out there.

The cameras look at five different social, open spaces within the building, register the movement of users throughout the day, and translate that footage into data points. I just get an object ID, a time stamp, and X, Y coordinates, which makes it completely anonymous. Then that data gets sent directly to a server in Denmark. From there, the data goes to a virtual network where I have a Python code that puts this data into my own database to collect and analyze it.

Because the cameras convert the video material directly to binary metadata, I have no idea of who it is that generated the data. So the cameras are fully compliant with GDPR regulations, the EU laws on data protection and privacy that were made in 2016. That made the installation process and addressing privacy concerns much easier.

What do you plan to do with the information we get from this study? How might it influence the practice of architecture in the coming years?

Of course, we can’t change the building’s physical structure based on my results. The data will inform future designs, offering insight about the spatial use and layout in our interiors.

I hope this project can serve as a prototype for an interactive tool that can help us understand and model the equilibrium of how users move between open and closed spaces. And that’s sort of my plan at the end of the day, where I could use data like this to create an online modeling interface where people could adjust the spatial dimensions of their designs, and see how social behavior might shift as a result. Effectively, it’s helping map out the ideal spatial dimensions for certain activities – To see what room sizes, light level, acoustics and so on suit certain activities. This could be a way to create an interaction between the user and the data.

We have never quite been able to quantify social behavior in a scalable way, but with this, I might be able to scale things up and test hypotheses on a wider level. In the end, we want to find the common ground, even in social outputs. It’s about finding a balance between physical and social factors, and the relationship between the two. My research here helps explore our sense of interpersonal space, how that affects our behavior, and how architects can use that knowledge in the future.