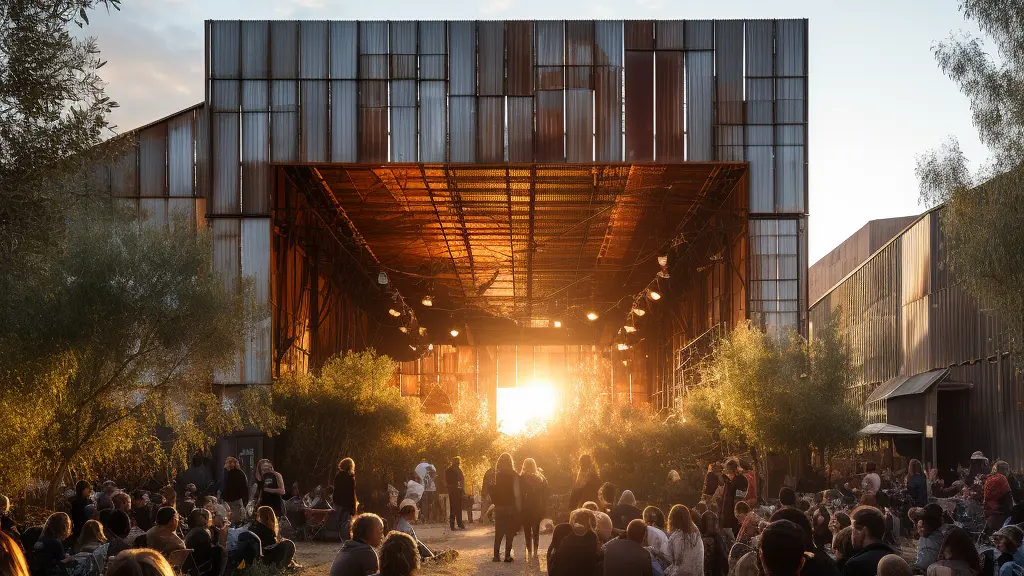

Embracing adaptive reuse: Can yesterday provide tomorrow’s solutions?

By Zoey Kroening

As the well-known statement goes “the greenest building is the one that already exists”, but how far has this idea reverberated? By reusing and transforming we have an opportunity to reduce the carbon footprint of the built environment, minimize waste and conserve resources, whilst preserving historical heritage and cultural value.

Contact

Katrine Daugaard Jørgensen

Head of Transformation

Magnus Reffs Kramhøft

Industrial PhD fellow, Architect

We hear from Katrine Daugaard Jørgensen and Magnus Reffs Kramhøft, as they spotlight the transformative power of adaptive reuse, shaping our approach to design with a focus on longevity, identity, creativity and sustainability.

Why do we need to turn our attention towards adaptive reuse rather than designing new construction?

Katrine: Adaptive reuse is the most direct and efficient way to save resources and (embodied) carbon. Through countless projects, I've discovered the immense architectural potential in transforming existing structures and envisioning them in a future context.

Magnus: For me, adaptive reuse is about transforming architectural practice into something less harmful and more meaningful. New builds can lack grounding and identity, but by focusing on the adaptation of existing buildings, we can create stronger architectural character and address the climate agenda. This approach allows us to embrace the inherent qualities of existing structures – narratives and materiality - preserving their history while adapting them to the future.

Our approach is not just to elevate but to reimagine the building in a way so that the past and present design work coherently together as one.

Katrine Daugaard Jørgensen

Head of Transformation

How is the creative approach and design process different when transforming an old structure compared to designing a new building?

Magnus: Existing buildings come with certain constraints, the structure needs to be dissected to understand its tectonics and the original intent behind it. Only then can we prioritize the necessary interventions and develop the design concept.

Katrine: The main difference between designing a new building and transforming something existing is that our design process is based on a deep understanding of the potential and limitations that lie within the building – both in regards to condition, materials, embodied carbon and its heritage. Our approach is not just to elevate, but to reimagine the building in a way, so that the past and present design work coherently together as one.

What are the main setbacks when it comes to adaptive reuse, and how can we overcome them?

Katrine: The conditions for preserving and transforming buildings in urban areas improve significantly when local regulations prioritize preservation over new build. The main challenges arise when the desired program does not suit the existing terms, leading to unnecessary budget costs with low value. Working closely with decision makers whilst doing the feasibility study allows us to identify and mitigate risks and adjust the project accordingly.

Another major challenge in transformation projects is preserving as much of the load-bearing structure as possible to maximize carbon savings, which can constrain space reconfiguration. Feasibility studies and creative thinking are essential to unlocking the full potential of a transformation and preventing it from becoming a stranded asset.

Some fear that restricting new construction is counterproductive, while others see it as essential for reducing the industry’s carbon footprint. Can we find common ground between new build and adaptive reuse?

Katrine: We must find common ground. Some buildings are in too poor a shape to be preserved, but we can address this by demanding that all demolition processes have ambitious resource management plans to create a circular economy. These specific cases are not the main problem; it is the widespread demolition that occurs before a building has reached its end of life. I strongly support legislative decision-making that demands the protection of buildings which are still in good condition. This will naturally encourage clients to find the best use for the building rather than defaulting to new build scenarios.

Magnus: The climate crisis demands a large shift in all aspects of how projects are handled. In the long run, we need to strive for a healthier development that also considers new value parameters such as climate, social considerations, or ecological concepts.

01/05

How do you balance the client’s needs with the possibilities presented by the existing structure?

Magnus: We should strive to work with the building, not against it. Therefore, it's crucial to align the client's needs with the opportunities offered by what is already present. This process includes everything from simple remodels to major structural alterations or additions to older buildings. It involves ongoing negotiation to align the project's vision and objectives. While it might not fulfill every initial desire the client has, prioritizing adaptive reuse often reveals new possibilities and embraces aesthetic imperfections, resulting in a dynamic, character-rich expression that new constructions can't easily replicate.

Do you believe we will reach a point where adaptive reuse surpasses new construction?

Magnus: I am optimistic that our sector is progressing towards more sustainable practices with greater knowledge guiding each step. Is it progressing fast enough? No. However, improvements occur daily, despite legislative and policy frameworks struggling to keep pace.

Most importantly there is an attitude change. I can certainly see adaptive reuse becoming as esteemed as new builds. Embracing and cherishing the challenges inherent in working with existing buildings is essential for decarbonization. This extends beyond our lifetimes; to me it is a reminder that we are entrusted with preserving and passing on what previous generations have created. For instance, when we have a greater appreciation of the ‘old’ we gain a deeper understanding of materials and building techniques, bridging the gap between digital tools and hands-on craftsmanship.

Embracing and cherishing the challenges inherent in working with existing buildings is essential for decarbonization.

Magnus Reffs Kramhøft

Industrial PhD fellow, Architect

Katrine: While there is a steep learning curve ahead, especially for contractors, authorities, and legislators, the increasing number of clients prioritizing adaptive reuse over new builds is promising. The industry's growth in transformation projects reflects this trend, and I remain hopeful for a future where adaptive reuse is prioritized over new build. Limitation has never been detrimental in terms of creating excellent architectural work.

It's incredibly rewarding when new architecture and existing structures merge and come together as a new, coherent design language. This will lead to nuanced and multifaceted architecture, making a greater contribution than the vast, generic architectural landscapes we often see today.

1970